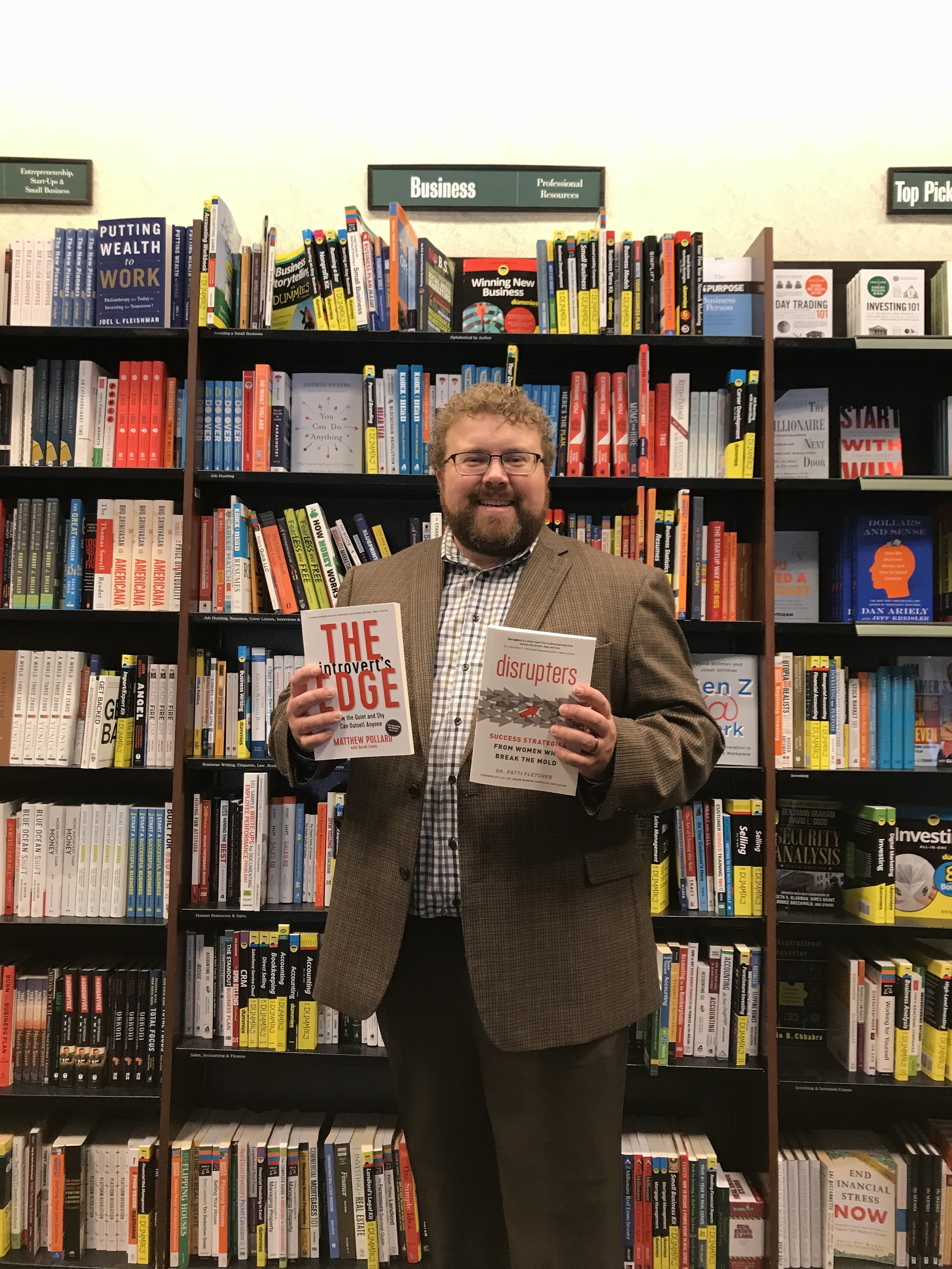

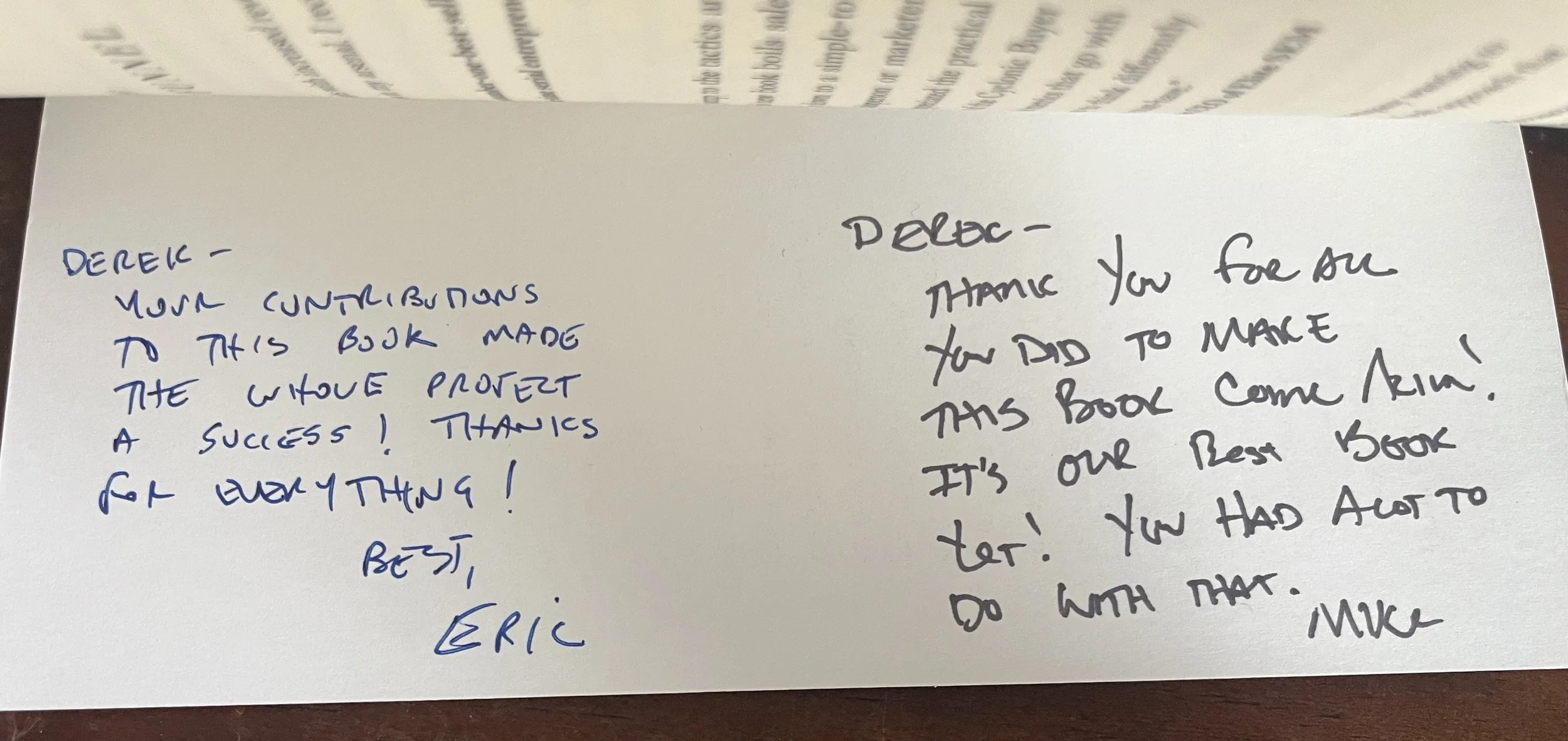

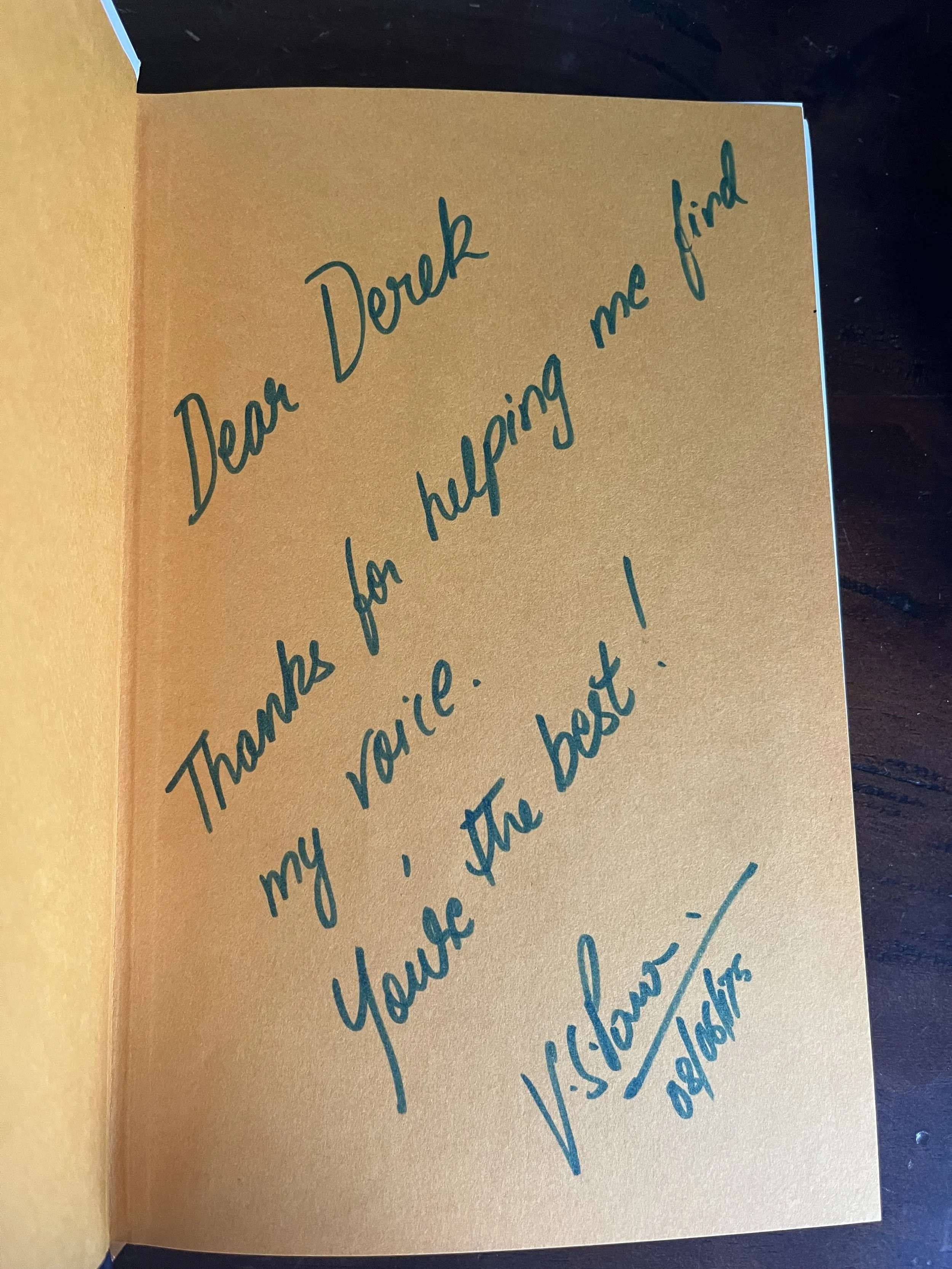

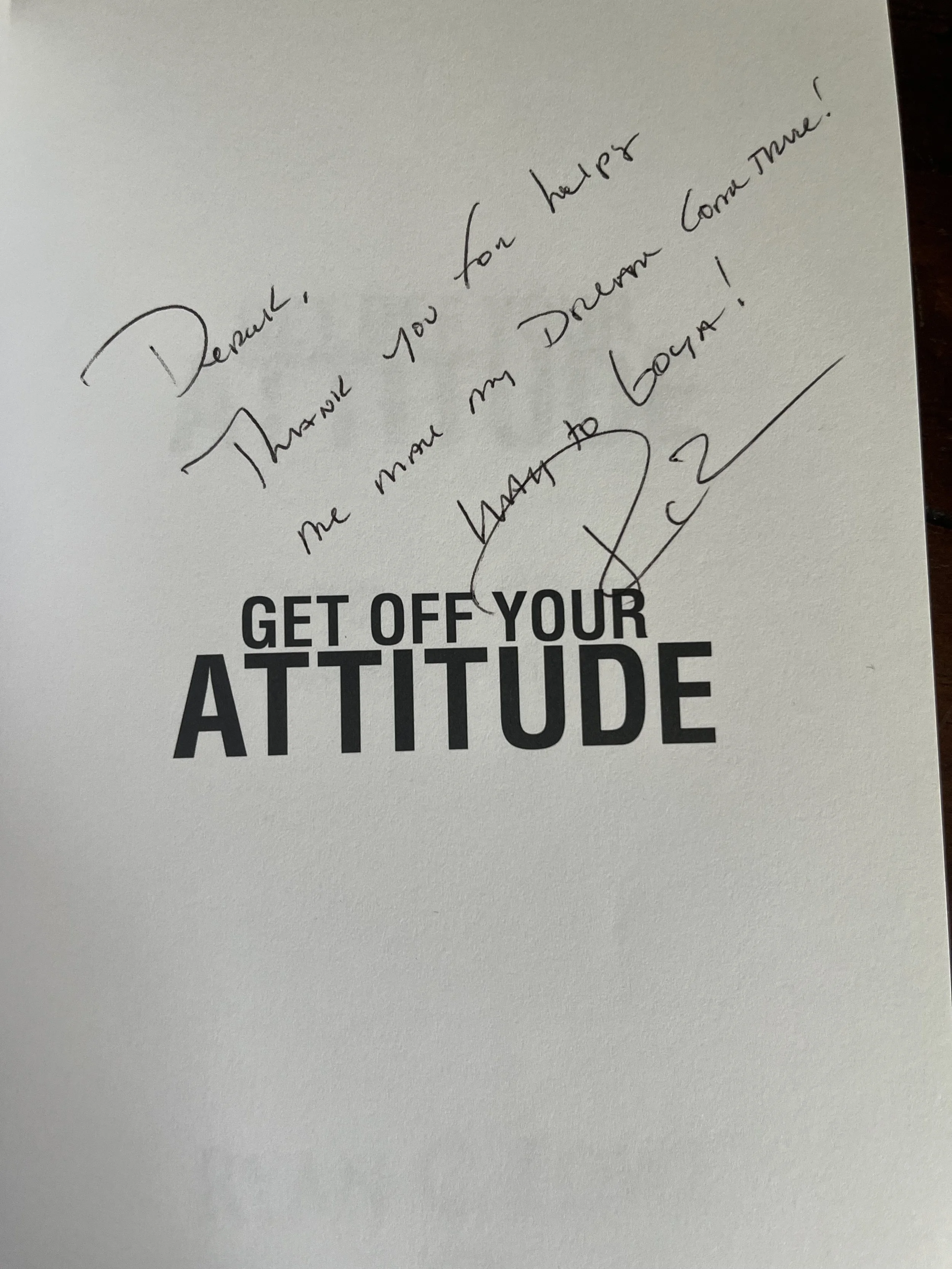

Business Book Ghostwriter for Experts and Entrepreneurs

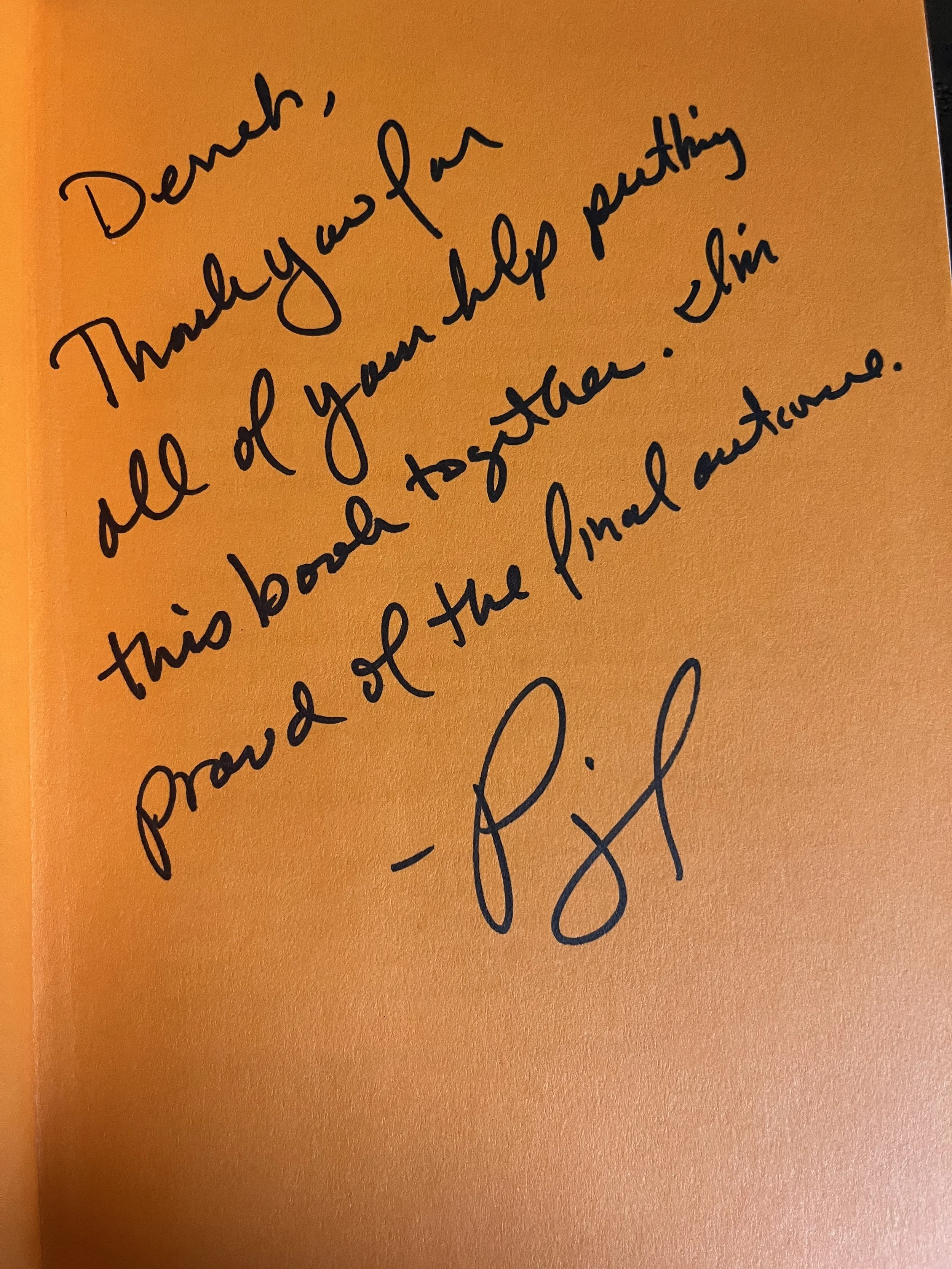

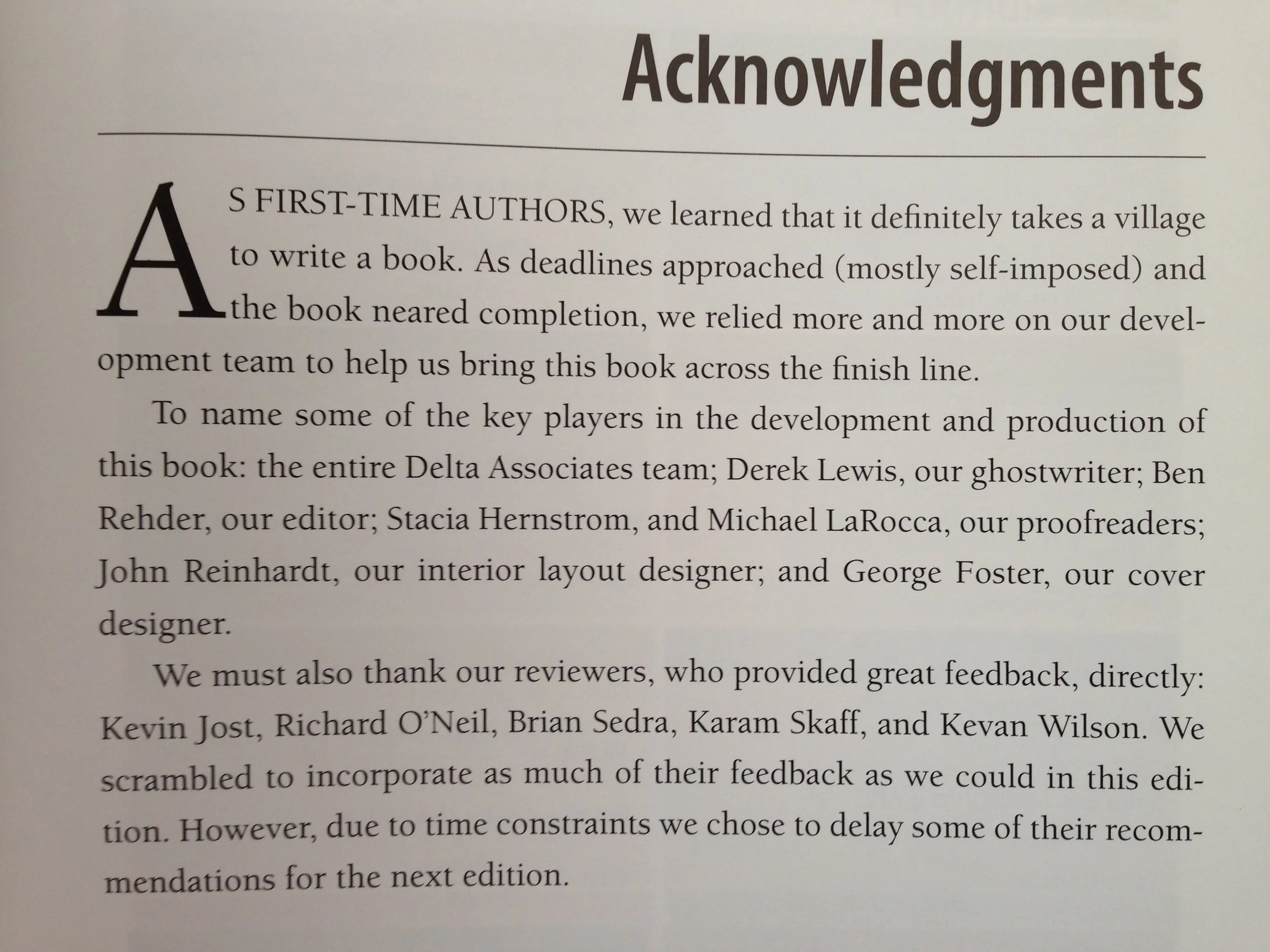

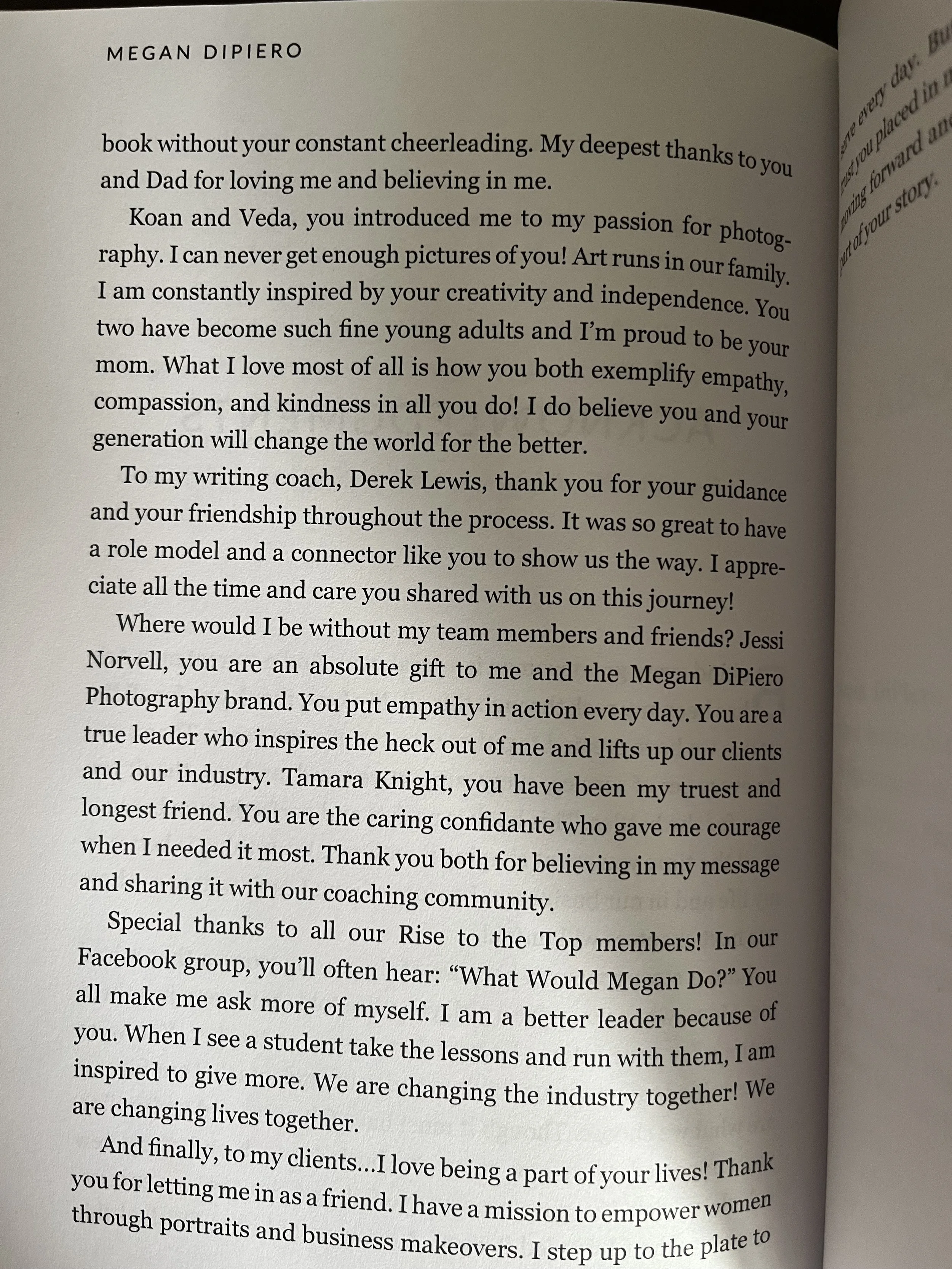

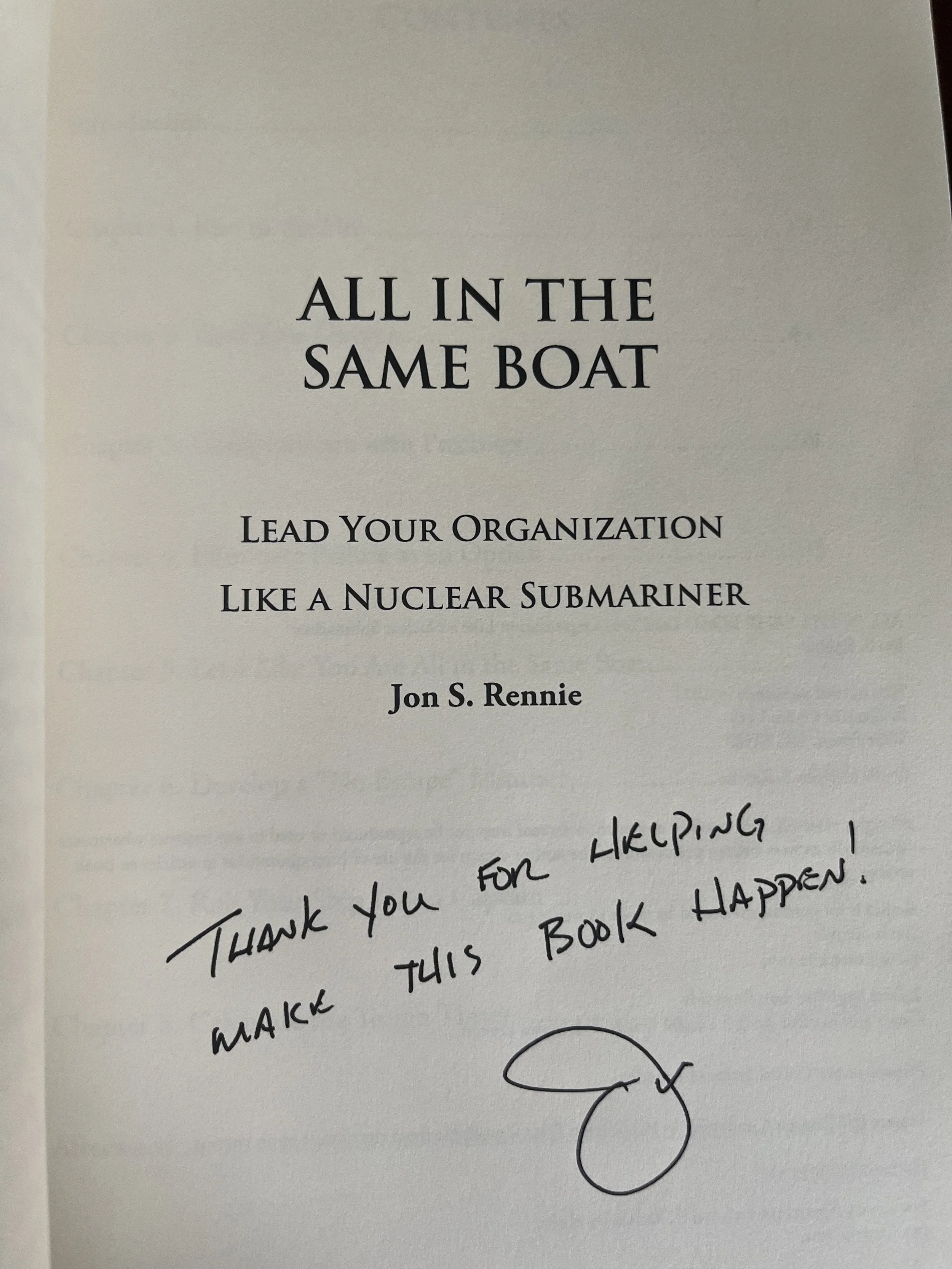

*No, I didn’t ghostwrite all these books. For some, I was the author, an editor, a consultant, or the coach. On the other hand, I can’t share all my ghostwriting projects nor every manuscript where I’ve been a catalyst.

Dear Expert/Entrepreneur,

You’re here because you’re writing a business book.

Or should I say you’re here because you haven’t written your book?

Because if you could have written your book, you would have written your book.

My name’s Derek Lewis, and I’m here to tell you there are two ways to go about it: the normal way and the fun way. Let’s talk about the normal way. Or, as I like to call it…

The Hard Way:

The High School Essay Approach

While you were in school, your teachers taught you how to write a report.

Pick your topic, do the research, write an outline, and then write your essay. Maybe you read over it once or twice before turning it in. Done.

That approach is essentially the same one we use for all of the “important” stuff we write in life and business. Blogs, articles in trade journals, findings summaries, consulting recommendations, and the like. You write an outline and then fill in the blanks.

It only makes sense that you do the same

when writing a book, right?

Yeah, how’s that working for you?

You’ve wrestled with the idea of writing a book for several years. Decades maybe. The task is daunting. You face the challenge of wondering whether you are good enough, know enough, or are interesting enough.

From time to time, you sit down at your computer, excited and full of energy. You begin typing away. It’s fun for a while. But as your inspiration dissipates, so, too, does your motivation. At some point, when you sit down at your computer, your mind goes as blank as the screen.

Where did all of it go?

You know enough to write a book. Or, at least, you used to believe that. Now, you question if you might be better off writing a blog post or a white paper.

How is it that while going about your daily business, you have so many great ideas that cross your mind and can’t wait to share those insights…but in front of your computer, writing feels like pulling teeth?

So, you put the idea on the back burner. From time to time, you get a fresh jolt of inspiration and have another go at it, only to see your enthusiasm begin to wane.

You tell yourself, I just need the right…

app, so you buy Scrivener

pen, so you buy a Mont Blanc

tool, so you buy a Pomodoro timer

notebook, so you buy a Moleskine

Unfortunately, none of those seems to do the trick.

I need to be more disciplined, you tell yourself. To really get this book out, perhaps you believe you need to set aside dedicated time every week. You buy books on how to write and stay motivated. You think that if you’ll set goals and reward yourself accordingly, it’ll trick your subconscious into wanting to write.

In short, you believe that if you just do more, you’ll finally write your book.

If you happen to be one of those Zen-like masters of military discipline, then maybe. Maybe you’ll make serious headway. Maybe. But how many professionals do you know who want to write a book? Who say they’re already writing a book? How many of them eventually publish it?

Regardless, you probably start writing your business book the same way virtually everyone does: at the beginning.

You spend weeks wrangling chapter one into some semblance of order, then spend more time polishing it to perfection.

And then you have to do all that again for Chapter Two!?

The way ahead seems dull or even dreadful.

If only there were a better way.

You say to yourself, “I know! I’ll use AI!”

Bill Gates once said, “The first rule of any technology used in a business is that automation applied to an efficient operation will magnify the efficiency. The second is that automation applied to an inefficient operation will magnify the inefficiency.”

AI is a fantastic tool. Like all tools, it has its uses as well as its limitations. Like all tools, it’s only as good as the person who wields it. Like all tools, it cannot think for you.

The normal way to write a business book has a fundamental flaw. As Gates’s quote suggests,

using AI to automate a fundamentally flawed approach only magnifies the flaws.

If you don't know how to put a good book together,

AI isn't going to magically solve that.

Ann Loring wrote,

“Good writing does not come from fancy word processors or expensive typewriters or special pencils or hand-crafted quill pens. Good writing comes from good thinking.”

So, please allow me to show you how to

think differently about writing.

Frankendraft™: The Better Way to Write Business Books

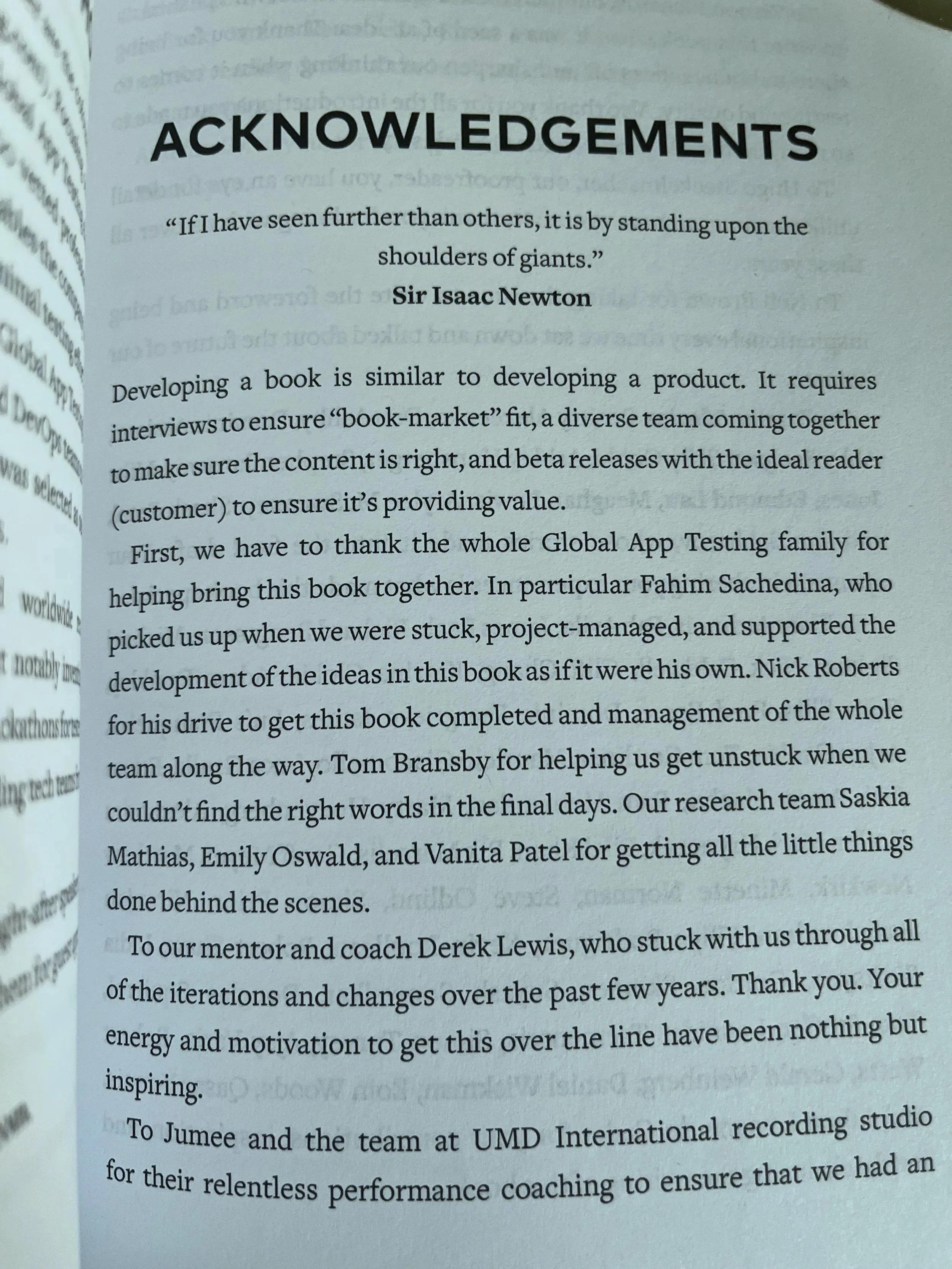

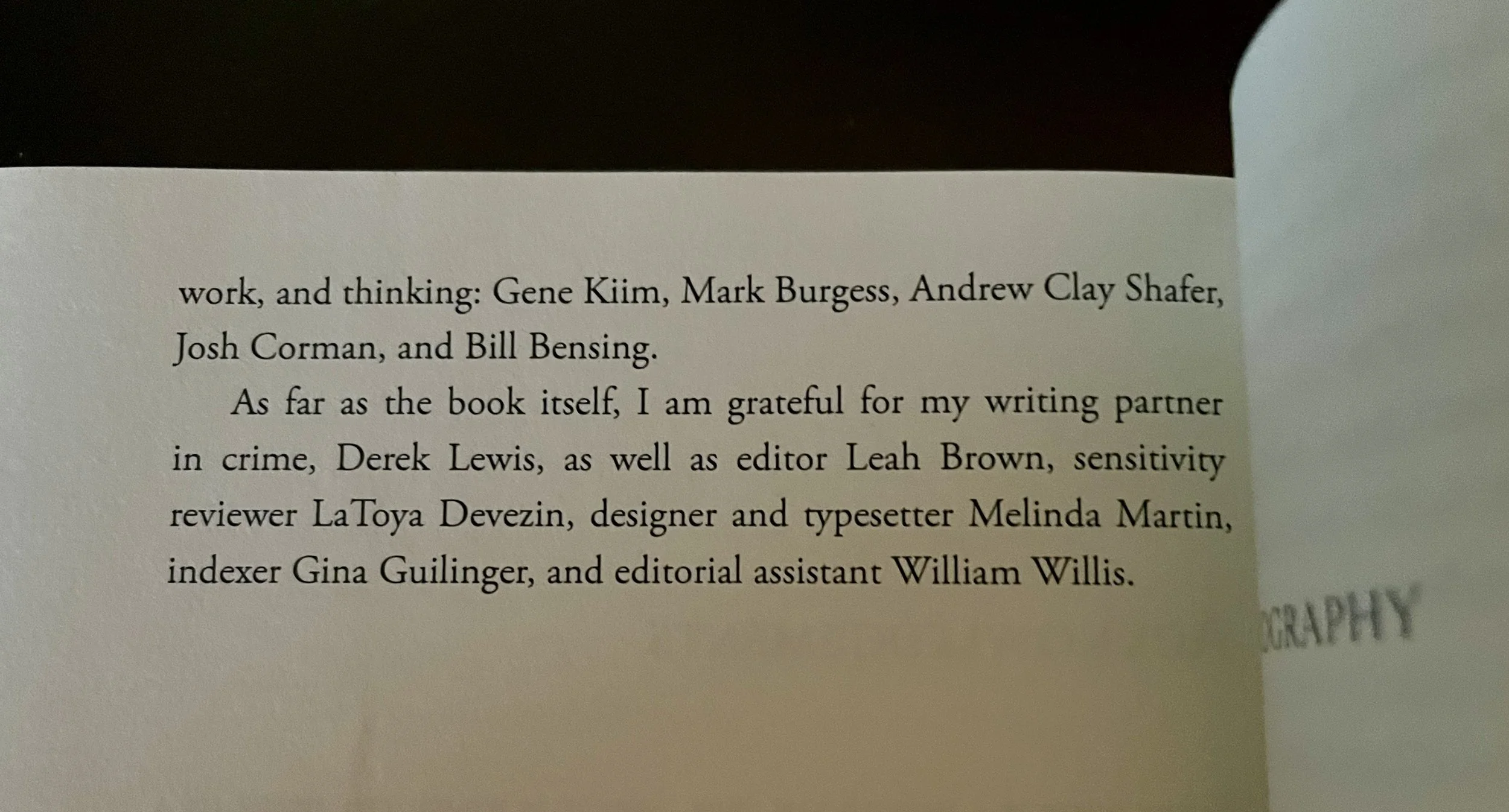

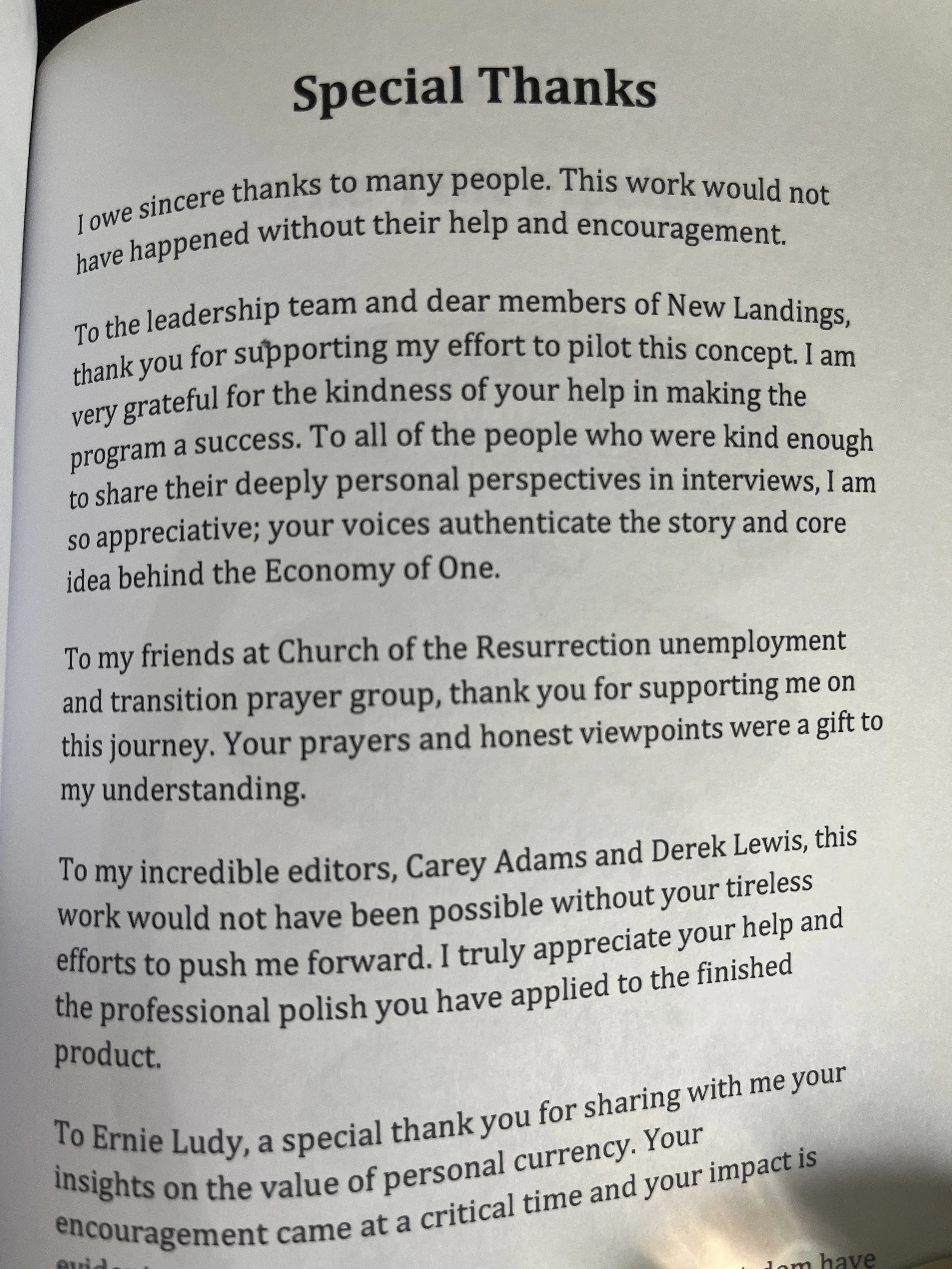

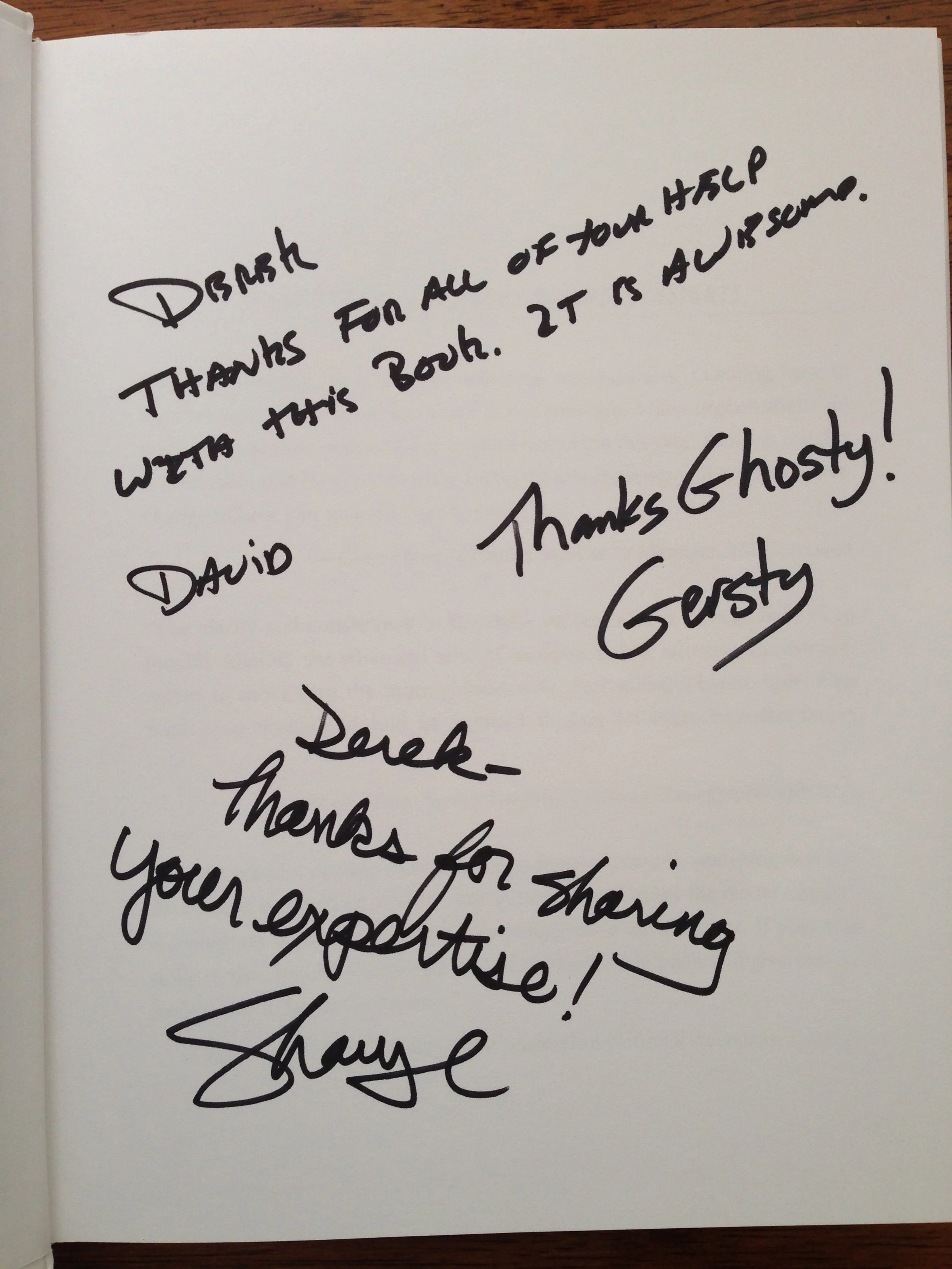

I’ve been working with manuscripts—ghostwriting, editing, coaching, consulting, co-authoring, collaborating, and discussing—for 16 years. I have tried everything.

Believe me, I know what don’t work.

(Yes, that error was intentional.)

I would love to pretend that I sat alone in a cabin in the woods on a mountaintop and descended holding the 5-step Frankendraft Method etched on tablets of stone. The truth, as usual, is not nearly so neat.

No, my Frankendraft approach came as a result of trial and error. Lots of trials. Plenty of experiments. A lot of writing, rewriting, and revising.

I’ve tried everything. I threw out what didn’t work and clung desperately to what did.

Frankendraft is what survived the abyss.

Frankendraft™, Step 0: The Mindset

I used to call it my 5-step “process” because anything more than that sounded pompous. After looking closer at the differences between the two words, I realized “method” captures it better. Frankendraft isn’t a set of linear steps.

Some tech authors told me it sounded like Agile Development, which is an iterative approach to creating software. Others have told me it reminds them of the Lean Startup methodology.

More importantly, it is a mindset. The heart of the Frankendraft Method can be summed up in a handful of quotes.

“Most people think of creativity as being entirely about the arts—music, painting, theatre, movies, dancing, sculpture, etc., etc. But this simply isn’t so. Creativity can be seen in every area of life—in science, in business, in sports. Wherever you can find a way of doing things that is better than what has been done before, you are being creative.”

You are creating something. It doesn’t matter that it’s a book on tax law or quality assurance testing or an economic forecasting model. It’s still creating something that wasn’t there before. The sooner you embrace that, oh business book author-to-be, the sooner you can start acting like a creative person.

“I believe that what we want to write wants to be written.”

If you feel like you have a book inside you, let me put your wonderings to rest.

You do.

Buried somewhere in your mind, there is a book your subconscious has been working on for years. When I start a ghostwriting collaboration, I’m never worried about whether the author knows enough to fill a book. In fact, I’m not worried about creating a book at all. Taking Julia Cameron’s quote to heart, I know that my author’s and my task is really to uncover their book which already exists.

“I’m convinced that fear is at the root of most bad writing.”

I doubt Stephen King had business books in mind when he penned those words. No matter. That truth stands.

I’ll let you in on a secret I’ve discovered after working with scores upon scores of authors. Forgive me if it stings, but I wouldn’t be doing my job if I sugarcoated it for you.

The real reason you haven’t written your book is because you’re afraid.

You’re afraid of…

Not being good enough

Not being smart enough

Not being creative enough

Not being interesting enough

Telling a story that exposes too much

Being judged

Being misunderstood

Being singled out

If that’s too harsh, think of it this way. Believe me when I, as a professional creative, tell you that your writer’s block is simply fear in disguise. Fear strangles your creativity. That’s the heart of the problem. Whether you know it or not, as a human being, you are naturally creative.

Legendary music producer Rick Rubin wrote in The Creative Act, “Creativity is a fundamental aspect of being human. It’s our birthright. And it’s for all of us.”

Either Picasso or John Lennon (sources vary) said, “Every child is an artist. The challenge is to remain an artist after you grow up.”

That natural creativity wants to create a book. That’s the whole reason you feel, deep in your gut, that this is a book you’ve got to write. Your heart, mind, body, and soul want to make something. In each of us exists a wellspring of creativity. Creativity naturally flows from us.

Fear gets in the way.

As a coach, consultant, and friend, every time someone has come to me with a case of writer’s block, I gently work with them to uncover what they’re specifically afraid of.

In one poignant example, while working with a husband-and-wife team, the husband hit a writing wall. When we got on Zoom, I patiently kept prodding at his defenses, justifications, and frustrations until he reached an epiphany. In explaining a part of their undergirding philosophy in the book, the husband would have to reveal some family secrets. Fortunately, in this case, they were wonderful secrets. His father had sacrificed quite a bit for the uncle, aunts, and cousins in their larger family, but he didn’t want anyone feeling beholden to him. That is, his father wanted to keep his own good deeds hidden.

The inventor Charles Kettering once said, “A problem well stated is a problem half solved.” As soon as the husband voiced those unconscious fears out loud, the three of us found a great solution that would preserve his father’s unspoken legacy while being an even more powerful way to present the book’s underlying message.

I could provide another half-dozen such examples, but I hope you get the point. When you get your writing blocks out of the way—blocks that stifle and strangle your innate creativity—writing (and other creative impulses) will flow out of you.

Which sets us up quite nicely for the next tenet.

“Don’t get it right. Get it written, then get it right.”

Don’t worry about getting it perfect. Don’t worry about how it sounds. Don’t worry about how it reads.

There is a time and a place for editing. In The Business Book Bible, I admonish my reader to “Edit your writing until it’s so smooth the reader forgets they’re even reading.” But everything in its proper place. Editing doesn’t even start until the fourth stage of Frankendraft. The first 3 stages focus solely on getting it out of your head and onto the page.

If anything, “Don’t get it right. Get it written, then get it right,” sums up my approach to writing more than any other quote. Because we’re afraid it won’t be perfect from the start, we don’t even begin.

Can you imagine the world if other creatives did the same thing? We certainly wouldn’t have the technology we do today. No inventors ever got their creation perfect with their very first prototype. We wouldn’t have skilled trades because they wouldn’t be willing to be students first. Every now and then, a poet or lyricist writes something perfect in a burst of sudden inspiration, but that rarely occurs.

No. If we want to create something, we have to let go of our fear of being wrong.

The final tenet of the Frankendraft framework is what inspired me to call it such an odd yet memorable name.

“Writing a book is more like bringing life to Frankenstein than painting the Mona Lisa.”

By the time my client and I have their Frankendraft, it is not pretty. It’s not something they want to show their mother. Or most children, for that matter. One leg is longer than the other, the hands are 3 different colors, the stitches on its forehead barely hold its brains in, and it’s got bolts sticking out of both sides of its neck.

Metaphorically.

Realistically, there are dangling modifiers and unfinished chapters. I take Rick Rubin’s advice to heart:

“If you reach a section of the work that gives you trouble, instead of letting this blockage stop you, work around it. Although your instinct may be to create sequentially, bypass the section where you’re stuck, complete the other parts, then come back to it.”

If Frankendraft were clothes, it’d be disheveled.

If it were a house, it’d be condemned.

Were it surgery, it’d be a malpractice suit.

As Robert Cormier wrote,

“The beautiful part of writing is that you don’t have to get it right the first time, unlike, say, a brain surgeon.”

Speaking from experience, it’s a helluva lot easier to edit bad writing than to write something from scratch.

So, there’s the Frankendraft framework in a nutshell: Don’t be da Vinci painting the Mona Lisa. Be a mad scientist bringing Frankenstein to life. And have fun doing it.

The Story of Bringing

Deming’s Journey to Profound Knowledge

To Life

“We are, as a species, addicted to story. Even when the body goes to sleep, the mind stays up all night, telling itself stories.”

That’s from Jonathan Gottschall’s book The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human.

Study after study show that the single best way to impart information with the highest recall is by embedding the information in a narrative. In short, if you want someone to understand you and make the information memorable (“sticky,” as they like to say in marketing), wrap the info in a story.

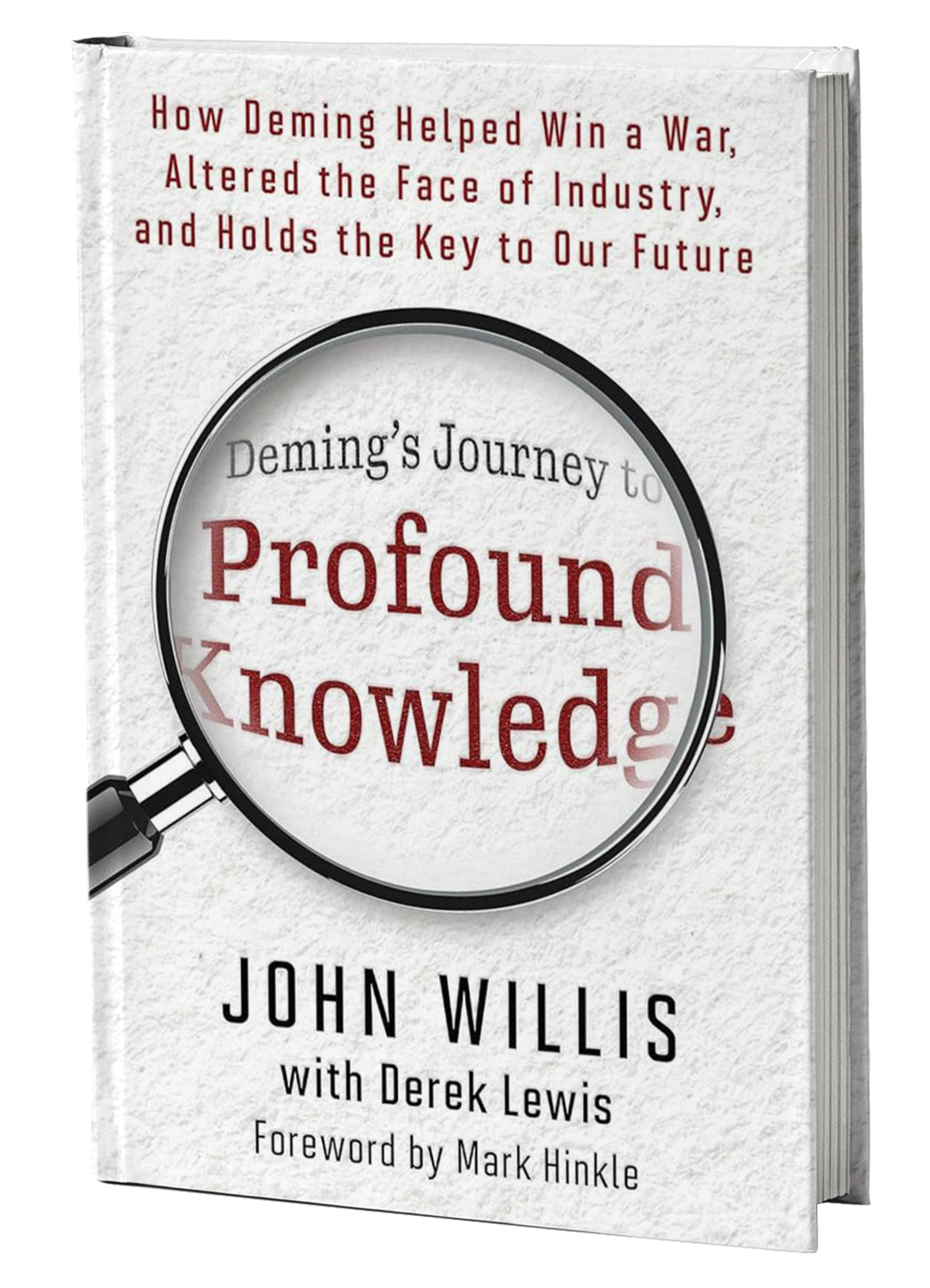

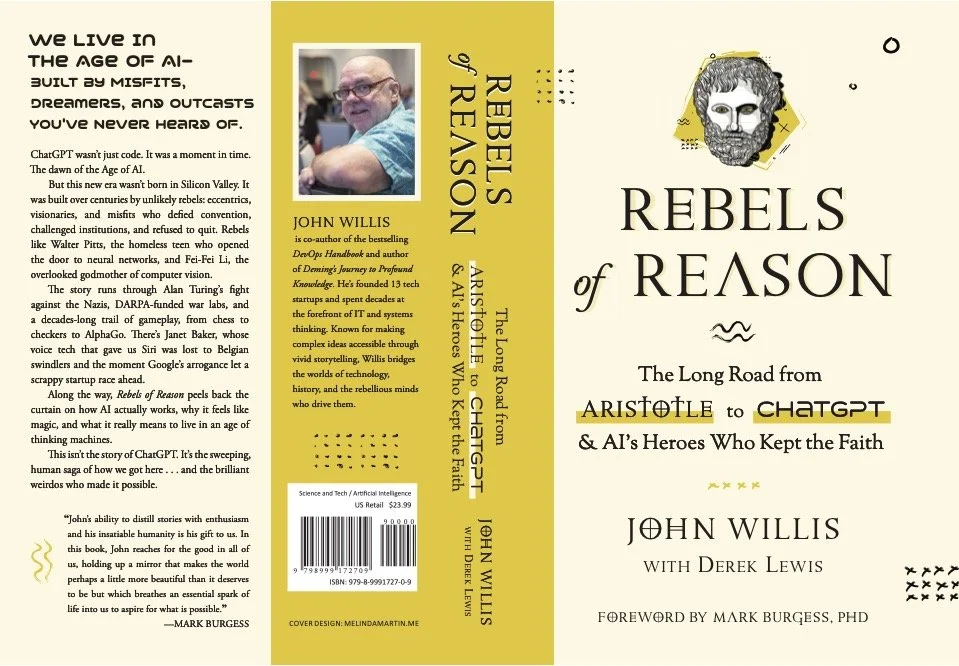

So, that’s what I’m going to do. I want to explain the Frankendraft framework, and I want you to remember it. To that end, I’m going to tell you the story of how John Willis and I collaborated to write Deming’s Journey to Profound Knowledge: How Deming Helped Win a War, Altered the Face of Industry, and Holds the Key to Our Future.

The Author, a Tech Entrepreneur

John’s been around the block. He started his career in tech over 40 years ago, working on Exxon mainframes with geological data as the company explored Prudhoe Bay. Since then, he’s co-founded 13 different tech startups with 6 successful exits. During that time, he became one of the 4 “godfathers” of the DevOps movement (a method of blending and accelerating workflows between the developers who create software code and the operations team who have to make the software work in the real world).

Many of the principles of DevOps came from lean manufacturing. The bible for that approach to production is The Goal, a business parable written in 1984. John read the bestselling classic and fell in love with all the writings of its author, Eliyahu Goldratt, who, in turn, had been greatly influenced by Dr. Edwards Deming.

In reading about Deming, John discovered that virtually all the books out there provided only some passing information about the man. Each spent the vast majority of the book explaining how to use his methods. Curious, he dug further and discovered that Edwards Deming had a fascinating story in his own right. By 2010, John started seriously playing with the idea of writing his own Deming book. Initially, he wanted to take Deming’s ideas and show how they could be applied directly to software development. That is, he envisioned a “pure” translation (instead of DevOps’s translation of lean manufacturing’s interpretation of Goldratt’s understanding of Deming). He also kicked around the idea of doing a straightforward biography, which would have been a first for Deming. Then he thought about combining those ideas into one book. The first half would tell the man’s story while the second would speak directly to the DevOps crowd.

Over the next several years, as the book rolled around in the reaches of his mind, he came across the story of an unsung hero in healthcare whose work with Dr. Deming impacted innumerable hospital patients, touching countless lives. Then, John found the obscure story of Hawthorne Works, which was essentially the 1920s’ Silicon Valley. Too, he found the untold story of Deming’s wife, a fellow statistician, who created the standards for women’s clothing sizes manufactured in the U.S.

For 10 years, John collected stories, anecdotes, examples, explanations, and applications by or related to Edwards Deming. At the end of that decade, he had a mountain of raw material.

But how was he going to turn all of that into a great book?

Enter the Ghostwriter

The year before John decided he would one day write a book on Deming, I hung my shingle as a book ghostwriter. Over the next eleven years, my adventures with my clients took me from Malibu to Miami, Boston to Barcelona. I start each ghostwriting project off with a 3-day author retreat. Those retreats have taken me to a chalet in the Swiss Alps, an industrial tech space in London, a business suite in Mexico City, and a villa in Mallorca, not to mention from Miami to Malibu.

My past clients include a Zumba founder, a billionaire plumber, several tech entrepreneurs, an economist with the International Monetary Fund, a chopper pilot in the Korean DMZ, a DC lobbyist, and a secretive Swedish boutique consultancy.

Then the world went to hell.

When COVID-19 broke out, John quickly quarantined himself at his lakehouse. With his worldwide travel suddenly curtailed, he found he had an extra 60-plus hours a month free. He decided it was now or never.

He knew he wanted someone to collaborate with. For advice, he reached out to Todd Sattersten, the man who turned tech entrepreneur Gene Kim’s budding book business into a publishing house. Todd sent John a short list of people he trusted who could help. Fortunately, he included my name on that list.

In our first call, I walked John through my Frankendraft framework. He was hooked.

“That sounds fantastic. I talked to a ghostwriting company and they said someone would interview me and then come back in 3 months with a book. I asked if they could do it differently, but that’s how they do all their books. That doesn’t work for me. Not with a book like this. This is perfect. When can we start?”

My next project slot wasn’t for another 11 months.

He couldn’t wait. The book was burning a hole in his soul. He had to get it out. He thanked me and went looking elsewhere. He searched for weeks…and it did not go well. With one ghostwriter, after John explained his idea, the guy wanted to switch from fee-for-service to a royalty split. In talking to another ghostwriting agency, John suspected it was the front for some kind of Russian mafia scheme. (Cool story.) He kept running into such dead ends.

Watching his growing frustration, his precious wife, Vicki, said, “Well, hasn’t it been about a year since you talked to that ghostwriter you really liked?”

Lo and behold, it had. He rang me again and fortune favored us. We started about 6 weeks later.

Frankendraft™,

Stage 1: Grave Robbing

As I state in The Business Book Bible, “Don’t start writing your book by writing your book.”

In the normal way to write a book, you start with chapter one. With Frankendraft, we start by digging through your subconscious. (Think of Igor grave-robbing to find the different pieces that would come together to form Frankenstein.) As John Cleese (Monty Python, Fawlty Towers) wrote,

“When we’re trying to be creative, there’s a real lack of clarity during most of the process. Our rational, analytical mind, of course, loves clarity—in fact, it worships it. But at the start of the creative process things cannot be clear. They are bound to be confusing.”

In my author retreats, I tell my clients, “Think of this as me holding you by your ankles and shaking you to see what falls out of your pockets.”

Since COVID-19 still reigned in terror, I conducted my first retreat via Zoom.

Retreat Day 1: Stream of Consciousness

Think of the first day as unleashing your subconscious. We spoke for hours about what had sparked the book in the first place, what he’d learned over the years, what he wanted in the book, discussions he’d had with people, applying Deming’s principles to DevOps, and anything remotely tangential to the book. John spoke off the cuff about everything he had learned, thought, pontificated, pondered, and wondered over not just the last eleven years but over the course of his career. I asked a thoughtful question here and there, but mostly prodded him to ramble.

As John Cleese’s quote just said, there is no clarity at the beginning of the creative process. I’ve found that authors rarely visit their fundamental assumptions.

With one AI genius, for example, he’d written a manuscript that was, in essence, a technical manual. In his retreat, though, we discovered that he truly wanted to write a manuscript for his children to guide them on how to embrace the arts even as AI disrupted the world. Those were two very different books. Related. Overlapping. But distinct.

That’s why Day 1 was given over to John’s stream-of-consciousness. Those “ramblings” were me giving his subconscious an opportunity to share what was buried in the recesses of his mind. You read above about how I believe the book you want to write wants to be written. John’s and my job was to bring it to the fore of his consciousness as whole and intact as possible.

Retreat Day 2: Facets of the Diamond

“I believe this is one of the oldest and most generous tricks the universe plays on us human beings, both for its own amusement and for ours: The universe buries strange jewels deep within us all, and then stands back to see if we can find them.”

John’s book on Deming was one of those gems. Stream-of-consciousness is the most powerful tool for digging that gem out. In Day 2 of John’s retreat, I used an assortment of other tools to examine the different facets of that jewel.

Over the previous 12 years, I had developed a number of exercises after working with a few dozen authors like John. While the exercises made rational sense on the surface, their true purpose was to prod John’s subconscious further. Exercises such as:

The One Reader

100 Awful Titles

The Hidden Buyer

Human Resources

Crash and Burn

Jaws in Space

Friends, Fools, and Foes

My absolute favorite game to play is Devil’s Advocate. I get my author’s permission to be a snarky, combative, smart-aleck agitator (which probably says more about me than I care to admit). It’s similar to Toyota’s “5 Whys” tool where you keep digging further down to the core of an issue or cause. The game wasn’t because I’m a sadistic service provider, but because I wanted to challenge John’s thinking and decisions. Not necessarily to dissuade him from anything, but to help us find the edges of the map, if you will. It’s as important to know what’s not the book as it is what’s going in the book.

So, Days 1 and 2 are all fun and games.

Day 3 is where it starts getting real.

Publisher Portfolio

Retreat Day 3:

Working Decisions

Directions

Another core tenet of Frankendraft says, “Everything is a placeholder.”

Until the first copy of your book has printed and shipped, nothing is final. Nothing is set in stone. Everything exists in a state of flux.

As we go through the stages of the Frankendraft framework, we become more and more confident in our work, but we do not become married to any one idea or decision. We allow our work to breathe and for our creative minds to rest.

Allow me to again quote from Creativity: A Short and Cheerful Guide. John Cleese relates a story about how he and a friend had written a comedy but Cleese misplaced it. Undeterred, he rewrote it from memory. Some time later, he found the original version. To his utter astoundment, his rewrite was far superior to what he’d first written. He said, “I was forced to the conclusion that my mind must have continued to think about the sketch after Graham and I had finished it. And that my mind had been improving what we’d written, without my making any conscious attempt to do so.”

He decided to do a few experiments. After several successful tries, he observed, “If I put the work in before going to bed, I often had a little creative idea overnight. …I began to think to myself, It can only be while I’m asleep, my mind goes on working at the problem so that it can give me the answer in the morning.”

This is one of the reasons I like to stretch the author retreat over multiple days. We start removing the author’s blocks so that their natural creativity begins to flow. Their subconscious mind begins churning out new and amazing ideas. In fact, this happens throughout a ghostwriting engagement. The more we consciously work on an author’s book, the more their subconscious will unlock.

That’s why Day 3 is not about making decisions, per se, but about settling on working directions. As in, which way should we start directing our focus? What are we going to use as a placeholder for this particular thing?

Like the book’s title. John and I wrapped up the retreat with a working title, but he was open to the fact that we might come up with a better title later. We had a rough outline of how the book might come together, but we were absolutely certain it would change. Day 3 really revolves around setting the starting point.

“Everything is a placeholder” is more of a mentality than an absolute rule. Publishers don’t want to hear a week before the book’s release date their author say, “You know? I think I need to rewrite the second half.” The further you go along in any process—building a house, developing software, creating a new product—the more difficult it is to make changes.

On the other hand, it's a pretty important principle. If you get halfway through the book and realize you're writing the wrong book, you have to embrace that fact. If you write a book that's anything less than what your gut tells you it needs to be, you'll never be happy with the result.

That’s my experience, anyway.

Truthfully, though, in the Grave Robbing stage, nothing really matters. In fact, nothing really matters in the next one, either.

Frankendraft™,

Stage 2: The Sandbox

I already said that you don’t start writing your book by writing your book.

Even here in Stage 2, we don’t begin writing your book. I mean, we begin writing…just not really writing.

After recording our conversations during the author retreat (and all subsequent meetings), John and I began to play around in what I now call the Sandbox.

In the other way to write business books—the High School Essay approach I mentioned earlier—once you decide on your topic, you then create an outline.

I don’t like outlines.

For business authors, at least, outlines tend to be quite rigid. You decide on your book’s structure from the outset. You create a series of bullet points and sub-points. Once you have your outline in hand, you simply expand on those bullet points and voilà! Your book’s written!

Yeah, if it were that easy, you wouldn’t be here and I wouldn’t have a job.

It’s great to have some idea of where you’re going before you get in the car, but one of my favorite sayings (which I am humbly proud of) is, “The act of creation is inherently chaotic.” At this point, John and I still weren’t sure exactly what we were writing.

He knew he didn’t want it to simply be a biography, though that would have been a worthy endeavor. Neither did he want yet another book explaining Deming’s principles, even if he would be the first to do so for software development. We were traveling to an unknown destination. The best we could hope for was to make course corrections along the way. And, most importantly, to have fun along the way.

In the delightfully helpful book Save the Cat!, Blake Snyder wrote,

“You must try to find the fun in everything you write. Because having fun lets you know you’re on the right track”

I am a serious believer in listening to the author’s gut. If John’s said this book wasn’t a biography but wasn’t a how-to manual either, then I listened to that.

So, if we didn’t have a destination, how do we make progress to get where we need to be?

“All art is a work in progress. It’s helpful to see the piece we’re working on as an experiment. One in which we can’t predict the outcome. Whatever the result, we will receive useful information that will benefit the next experiment.”

Everything is a placeholder. Everything is a discussion doc. We throw paint on the canvas. We throw spaghetti at the wall to see what sticks. Everything is an experiment.

What I write in Stage 2 defies easy explanation. It’s more and less than a conventional manuscript outline. I tried calling it “the blueprints,” but that connotes fixed and rigid plans that the builders follow religiously. The things I produce look different for every project. With some books, it does look more like a structured outline. With others, these scribblings more resemble the rantings of a mad scientist: disjointed, jumping from idea to idea with no apparent bridge between. With some authors, I’ll write a kind of mini-chapter with one page or so per proposed chapter. Sometimes, we won’t have chapters in mind and I instead group material into “buckets,” a.k.a. the major chunks of the book without clearly delineated chapters. How can you standardize something that looks different with every new book project? I’ve experimented with a number of ways to describe this stage:

Expanded table of contents.

Sketch.

Scale model.

Maquette. Mini-book. The Mock-Up.

The Lab. The Forge. The Studio. The Workshop.

Coincidentally, it was John who (much later) helped me settle on the name that best captures the mindset and reality of Stage 2: The Sandbox.

Once again, I must quote from one of the most down-to-earth guides to this kind of work I’ve ever come across: The Creative Act. Rubin wrote,

“Active play and experimentation until we're happily surprised is how the best work reveals itself.”

The entire process of writing a book should be fun, but Stage 2 is about having nothing but fun. John and I initially worked from a rough outline John had pieced together, but quickly began experimenting. We played with different voices, arranged the material in different ways, toyed with crazy ideas, and had a great time along the way. I ghostwrote some parts to get a feel for how we wanted to present the content. One of us (and throughout my collaborations, we get to a place where we truly don’t know who first proposed an idea, who took it and made it better, or who said one thing that sparked the other one) wondered whether Deming’s story should stop at his death. That idea led to the idea of melding Deming’s story into a how-to for DevOps by talking about how his ideas continue to guide development today.

Since the working direction of the book roughly followed the course of Deming’s life, going in chronological order seemed logical. But as I wrote in The Business Book Bible, “When you write the book, set the hook.” Every chapter should draw the reader from the very beginning; the start of chapter one, even more so. In this instant, I knew the book would not open with, “William Edwards Deming was born on…”

Yawn.

Fortunately, John already had the solution. He’d known for some time that one of the “anchor stories,” as he called them, would be the anecdote of Deming’s family in 1979 gathered around the TV to watch an NBC special report that featured Deming. knew Dr. Deming had traveled to Japan often on work trips, but the show revealed to them the fact that the quiet, diligent, hardworking grandfather had been instrumental in the Japanese Economic Miracle, the phenomenon whereby Japan rebuilt itself after World War II to become an economic superpower.

His wife, sister-in-law, and grandson had no idea the unassuming man who worked out of the basement of their DC brownstone catalyzed one of the most amazing rebuilding efforts in human history.

I ghostwrote the story as a one-page anecdote. On the next page, John and I created a list of potential topics, quotes, facts, ideas, and stories that made sense for Chapter 1. We did the same for an additional 14 chapters: an opening anchor story followed by a mishmashed laundry list of what else might go with it.

After Chapter 15, we had the glimmerings of a good book, but…something wasn’t right. I didn’t feel settled.

It’s hard to explain this to people used to relying solely on analytical thinking. They might believe a novelist should follow their gut, but a business book? Come on. It’s just making a logical argument supported by evidence. Right?

This comes back to believing—nay, knowing—the book my authors want to write exists in their subconscious. It’s there. We’re not creating so much as uncovering that fossil, buried under strata of mental pediment.

In comparing his original comedy sketch to the one he recreated from memory, John Cleese said,

“Your unconscious communicates its knowledge to you solely through the language of the unconscious. And the language of the unconscious is not verbal. It’s like the language of dreams. It shows you images, it gives you feelings, it nudges you around without you immediately knowing what it’s getting at.”

No, I didn’t have the answer to why the working outline we had didn’t feel…finished. Didn’t sit well with me. I didn’t feel settled or get that feeling of completeness. A sense of rightness.

Fortunately, John is also a musician and songwriter. He understands listening to your gut. In addition, he also trusted my process. He didn’t object when I wanted to take another trip through the Sandbox before getting to the “real” writing.

We fleshed out the anchoring narrative for each chapter and got more concrete about which ideas, topics, and concepts should be included. We realized we had crammed too much into Chapter 5, so we broke it in half. The manuscript-to-be stood at 16 chapters.

Still not right.

On the third pass through the Sandbox, we realized the first half of Chapter 4 should really be folded into Chapter 3. Chapter 5 became the new Chapter 4 and we were back to 15 chapters.

This time, we both felt good about how the book—with the working title Profound—was coming together. We settled on a voice that was smart without being condescending, excited without gushing, and warm without being patronizing.

At that point, it felt…right.

I don’t know how else to explain it. There’s no yardstick to validate that “yes, here is the correct spot to mark it with an X; we’ve discovered the treasure and our quest is ended.”

The time had come to Write.

Capital W.

Except not.

Frankendraft™, Stage 3: Frankendraft™

Yes, the name of Stage 3 is also the name of the whole thing. Keep up.

This is where John and I would begin to write the actual manuscript. It was time to finally start writing the real book. To Write, if you will.

Except, it’s really not that dramatic. Because of all the time we spent gathering building blocks during Grave Robbing and playing around in the Sandbox, it didn’t feel like we were finally beginning. We’d already sort of started writing the book weeks and weeks before—and John was having a blast doing it.

(I always have a good time. A writer who enjoys writing. Go figure.)

This is a hallmark of the Frankendraft framework: You begin writing your book without it feeling like you’re writing your book. You sort of stumble backwards into your manuscript without ever having felt the pressure of staring at a blank screen.

Another hallmark is that even writing a “serious” book feels fun.

I don’t mean to say writing a book is easy. It is incredibly hard, even for someone like me who does it for a living. But writing should be fun. And when you're having fun, it doesn't feel like hard work. It might feel challenging, but it's an invigorating type of challenge, like doing an extra set at the gym or spending that last half hour to be completely done with a project. At the end, you feel exhausted but, often, strangely exhilarated. Weary but with a sense of well done-edness. (Another made up word.) Gratified.

That's writing a book via the Frankendraft framework. Is it a challenge? Absolutely. Is it hard? Only if you're not having fun.

So, John and I began to write the manuscript draft—ahem—the Frankendraft together.

Today, John doesn’t call me his ghostwriter. It’s not that he’s ashamed to have worked with me.

Quite the opposite: “with Derek Lewis” sits right underneath his name on the book’s cover. As he explains it, "He wasn't my ghostwriter. He was my collaborator. By the end, he was more like my co-author."

My own ghostwriting mentor, the inestimable Claudia Suzanne, says a ghostwriter as someone who turns straw into gold. That is, a professional writer who takes someone’s rough draft and creates a great book from it. Truthfully, that is the better description of a traditional ghostwriter.

I generally come in before the author has a manuscript. I prefer this, actually, as I often find that authors have written the wrong book. Not that their book is wrong, per se, but what they’ve written isn’t what they actually wanted to write. It may be solid information with all the periods and Oxford commas in the right place, but it’s not the book they had in their heart. Earlier, I mentioned the example of the AI expert who wrote a technical manual, but during his author retreat discovered his heart told him to write a guide for young creative professionals like his children.

He wrote the wrong book.

I call myself a ghostwriter because that’s the easiest way to market myself. In truth, I’m more of a book collaborator. The writing partner. Co-conspirator. Whatever floats your boat.

I have often been the sole writing partner in a project, but more often than not, my authors are fine writers in their own right. In fact, the projects I enjoy best are those where my clients get their hands dirty.

Like John.

All together, he probably wrote about 100,000 words of original content. (If you did the math on our timeline, you might realize this was before ChatGPT came online. This was 100,000 typed words. Roughly half-a-million keystrokes. At least.)

He would rough in a chapter, then send it to me to “do the Derek magic,” as he likes to say. I would flesh out his writing, expanding and adding even more content. He and I would both research the content. In the end, I had reams of print-outs of websites, blogs, and books. I had an entire shelf of Deming-related books. Something like 16, at one point. John had nearly all those and more, plus ebooks.

Once I had a working version of a chapter, I’d send it to John. Then we’d have a Zoom call to discuss everything.

What he liked. What he hated. What he loved.

What felt on-target and missed the mark.

What sparked an idea, where we missed an opportunity, whether an explanation worked.

We conversed. We questioned each other. We went off on wild tangents. Like the Walrus and the Carpenter, we spoke of shoes and ships and sealing wax, of cabbages and kings, why the sea is boiling hot and whether pigs have wings. More often than not, we’d simply be in love with a section and, in talking about why, would come up with whole new perspectives, narratives, or experiments to perform.

Breathless, exhausted, and exhilarated at the conclusion of each feedback session, I would take all of our ideas, run back to my desk, and…not do any of that. No, not at all.

In Stage 3, you do not revise a chapter. It’s a rule. All of that feedback course-corrects for the next chapter. We do not go back to fix a chapter. It’s a waste of time. It doesn’t make sense to polish a piece of prose to perfection only to later discover it won’t serve the book’s purpose. We don’t even know what we’re doing yet.

Stealing yet another brilliant line from that resourceful book The Business Book Bible,

“You have to write your book before you know what you’re writing about.”

My ghostwriting mentor,

Claudia SuzanneYes, John’s vision for Profound was coming more into focus all the time, but the truth I’ve experienced time and again is that we don’t really know what book we’re writing until we’ve written the Frankendraft. We just don’t know.

Frankendraft chapters serve more as discussion documents than the words that will go to print. It’s a way for you to see your vision in black and white, then intuit what rings your bell and what falls flat. It gives you something to respond to. The clearer your vision is to you, the more I can translate that onto the page. We’re constantly course correcting. Creativity isn’t linear.

I’ll say again for the people in the back: Creativity isn’t linear.

If I could sum up Frankendraft in just 3 words, it would be, “Progress, not perfection.”

Momentum begets momentum. An object in motion tends to stay in motion. We don’t want to get bogged down in details, to have our enthusiasm wane and our energy flag. We’re looking to snowball your book, not trek up the mountain.

Of course, I made notes and transcribed our meetings. The feedback was invaluable. But I put it aside for later. We used our conversations as the starting point for the next chapter. John would continue to crank out raw content, and I continued spinning those threads into a more complete image.

When we were finished with Profound’s Frankendraft, it certainly lived up to its name. It was as profoundly ugly as Frankenstein himself. It wasn’t a proper manuscript draft. It was awful. It was disorganized. It was unfinished.

A train of thought would barrel off the rails. Paragraphs stopped mid-thought. Participles dangled like bats. The table of contents exploded from 15 chapters to 20. It had a look only a mother could love.

And John did. He loved it. I loved it.

But you know what we were missing?

The lightning.

Frankendraft™, Stage 3b:

The Lightning Strike

In every ghostwriting collaboration I’ve ever been part of, there’s a moment of epiphany. A realization. A revelation. One moment, everything’s normal. Out of nothing and from nowhere, a bolt of lightning flashes before us, illuminating the entire world. What was hidden before becomes blindingly obvious.

Nine times out of ten, I say, “Oh! That’s what the book’s about!”

To show you what I mean, let me tell you about Dr. Karin Stumpf, a consultant in Berlin who worked on the Daimler-Chrysler merger. About three-quarters into her Frankendraft, I said, “Karin, I know this book is ostensibly about your change management methodology, but after looking at all your stories, the advice you give, the way you speak to the reader…Karin, I think this is actually a change management leadership book.”

She said, “Hmm. Let me think about that.”

She disappeared for two weeks, and then came back. “You’re right. It’s really a leadership book.”

It may not sound like much of a change to pivot from a change management book to a change management leadership book, but take my word for it: Those are two fundamentally different books. But it felt right.

It’s like looking at one of those 3D images where the page seems to swim together until your eyes see juuusssttt right…and BAM! Out of the picture of a bad mushroom trip, a dolphin leaps from the page.

Reenergized by our jolt of lightning, we immediately dove back into the thick of it and…finished that version of the Frankendraft.

That’s another one of the rules of Frankendraft: We have to finish it. We may be champing at the bit to reshape all our work, but we do not abandon a Frankendraft midway through. Even knowing we’re writing the wrong book, we still finish the Frankendraft.

But John and I had not had that lightning strike. That’s the first time I’ve gotten through an entire Frankendraft without an epiphany. So, we went through Stage 3 again.

This prompted a whole new rule: No moving on to Stage 4 until the lightning strikes.

This round, it happened. John was explaining his book to a friend when the electricity surged through his fingers. Profound wasn’t Deming’s biography nor his methodology. The book was the story of how Deming discovered the four “lenses” of his System of Profound Knowledge, the legacy he bequeathed our world.

Of course!

The entire book fell into focus. While the narrative necessarily included the elements of his life and his approach to business, the story arc was about how the four elements of his grand system were discovered or revealed to him over the course of his life.

But the story didn't stop at Deming's unveiling of the System of Profound Knowledge. In the final section of the book, John was inspired to tell the story of how Deming's ideas paved the way for the Japanese Economic Miracle...of which Toyota was a part and what inspired lean manufacturing…which inspired agile development…which inspired DevOps, the movement of which John was one of the four pioneers. So, the story wasn't just Deming’s but John’s, too.

Thus, fulfilling one of the more difficult beliefs in creativity that Rick Rubin wrote about:

“The work reveals itself as you go.”

Or, as John Cleese shared,

“[The most creative people] are able to tolerate that vague sense of discomfort that we all feel, when some important decision is left open, because they know that an answer will eventually present itself.”

John had faith in me, and I had faith in the process.

After the lightning hit, we finished that round of Frankendraft (again, one of the rules), all the while eager to move on to the next stage.

Frankendraft™, Stage 4: The Rebuild

Once upon a time, I called this step the Rewrite.

Non-professional writers (that is, people like my clients) get nervous upon hearing that word. Rewriting sounds like a lot of work. And for many people, it is. But for professional writers (that is, people like me) writing is not the hard part. Knowing what to write—that’s the hard part.

Or, as Stephen Leacock put it, “Writing is no trouble: you just jot down ideas as they occur to you. The jotting is simplicity itself—it is the occurring which is difficult.”

Instead of the Rewrite, I tried using “the Edit” for a bit, but this stage comprises more than a mere edit. Going back to my mentor’s definition, this would be the point where normal ghostwriting starts. So, calling this step an edit would be a bit of a misnomer.

I settled on the Rebuild. It conveys more than simply an edit but doesn't sound as scary as a complete rewrite. And not all manuscripts require a rewrite. If the author had exceptional clarity of vision in the beginning, this stage was more of a substantive edit than an overhaul. But those authors were the ones who'd refined their ideas over years of teaching and presenting their insights to others; the exceptions, not the norm.

With Profound, while John and I kept much of the content from the second Frankendraft, we reworked the entire manuscript to align with our new vision. Also, the manuscript shrank to 19 chapters. Go figure.

I plan for multiple rounds in Stage 4. Or “passes,” if that’s easier to stomach. Here, it’s easy to see why Frankendraft is about “progress, not perfection.” There were stories that, while they were cool, didn’t significantly advance the arc of Deming’s Journey to Profound Knowledge, as our publisher would later title it.

(However, we loved those stories so much that we decided to self-publish a companion book, More Profound Stories, that included all the content we cut as well as some extra stories we’d come across. That mini-project in itself was pretty cool.)

Editing content we ultimately cut would have been a waste of time. Why perfect something we may end up round-filing? Why polish a piece of prose to perfection only to find it’s perfunctory?

Yet another quote from The Creative Act (and in case you’re wondering, yes, I have read other books on creativity; his just happens to be one of the very best):

“The initial inspiration has a vitality in it that can carry you through the whole piece. Don’t be concerned if some of the parts are not yet all they can be. Get through a rough draft. A full, imperfect vision is generally more helpful than a seemingly perfect fragment. ”

Exactly: A Frankendraft delivers a full if imperfect vision. That’s its whole purpose. From seeing the full picture, we can start making it pretty. Stage 4 is, as I often say, where the magic happens.

In The Business Book Bible, I said, “Writing is about knowing what to say. Editing is about knowing how to say it.” After the lightning strike and quickly finishing the Frankendraft, we go into editing mode.

Editing comes in three blurry flavors:

1. Developmental/substantive/structural/macro editing: Some professionals classify this level as two distinct ones, but again, the lines get blurry quickly. This high level focuses on the big picture. Do we have all the content we need? Is there any writing we don’t need? Are the chapters in the right order? Does the writing logically flow from one point to the next (or “slinky flow,” as my mentor calls it). That is, does the book make sense?

You read earlier that creativity is not linear. Well, neither is editing. While my focus starts with this level, I simultaneously keep my eyes open for opportunities to address the other two types.

2. Line editing: My mentor calls this “musical line editing,” and what a beautiful descriptor. “Okay, the manuscript makes sense…but is it beautiful?” Do the words roll off your tongue? As I wrote earlier, “Edit your writing until it’s so smooth the reader forgets they’re even reading.” Is every paragraph, sentence, fragment, and word as sweet, succinct, and compelling as it can be?

I once edited an author’s manuscript from 80,000 words down to ~60,000 without really changing a thing. It broke his heart to see so much of his hard work go down the drain (it didn’t, but it felt that way), but after reading it, he had to admit the edited version was clearer and more compelling. Saying the exact same thing in 25% fewer words made his book even more convincing and informative. That’s line-editing.

If you go it alone following the Frankendraft Method, don’t despair if you’re not a professional writer. If you can’t hire a professional editor, don’t let it stop you from sharing your insights with the world. As a Chinese proverb says, “Better a diamond with a flaw than a pebble without one.” Your book doesn’t have to be perfect to publish.

Fortunately, John had me, and I do a decent enough job.

(The final level of editing comes in Stage 5. We’ll get there in a minute.)

Could we have spent another round line editing? Yes…but that’s always true. You can always make a piece of writing better. Some novelists spend years polishing their manuscripts into works of art of exquisite beauty.

But Profound was a business book, and at some point, enough is enough. As Rubin says, “The work is done when you feel it is.”

We felt it was done.

Which, of course, it wasn’t. But we have to feel it’s finished before we can move on to the next part.

Frankendraft™, Stage 5:

Pitchforks and Fire

As Dr. Frankenstein brings his creation to life, the villagers storm the castle.

The fifth and final stage of the Frankendraft framework focuses on readying your manuscript for the mob at your door. The angry masses demanding you finally show them what you’ve been working on for months.

Way back in the author retreat, John and I had identified a handful of people to be what I call alpha readers. (I’ve since discovered I wasn’t the first person to riff off what publishers call beta readers. And here I thought I was an original.) Alpha readers are people so invested in your success that they’ll be truthful about how ugly your baby is.

Americans, it seems, have a penchant for avoiding direct criticism. As a society and on the whole, we are conflict avoidant. We don’t like to be the bearers of bad news. I mean, we invented the compliment sandwich, for chrissakes. Sheesh.

The very first people to read your manuscript have to love you enough to be honest with you. Think of a maid of honor telling the bride not to buy a particular wedding dress, even if the bride-to-be loves it. After battling depression for years, an “athletic fit” shirt would make me look like the watermelon in those videos where people see how many rubber bands they can fit around the fruit before it bursts.

Real friends tell us the truth, even when it hurts.

John could have found dozens of people who’d come back to us and say, “Oh, wow, guys. Good job. Loved it.” While encouraging, that feedback’s useless. Less than useless, really, because it would only reinforce us wearing our rose-tinted glasses while reading.

We needed John’s best friend, Curtis, telling us to stop using so many $%@# em dashes. (I’m fairly sure ChatGPT learned to do that from reading my earlier work. I never thought the em (—) dash got enough love until AI hit the streets. Nowadays, people automatically assume AI wrote something when they see that previously unknown punctuation mark. I can’t win for losing.)

All 4 of John’s alpha readers said there was something they didn’t like about Chapter 3, which floored us. The piece on Deming’s time at Hawthorne Works had been one the three anchor stories John had come to me with. After collating everyone’s feedback, we read over it several times.

Some things seem obvious in hindsight. Chapter 3 certainly was. We opened the chapter with a neat story about Tracy’s Rock when a lunar astronaut spelled his daughter’s initials in moondust just before leaving to come home. The man’s mother had paid for his education, in part, from her years on the assembly lines at the Hawthorne Works factory.

Fascinating fact.

Superfluous story.

We polled one of the alpha readers whether removing it would solve their problem with the chapter. After quickly looking over the chapter again, they came back with an enthusiastic, “Yes!”

And this is why we have alpha readers.

With all their feedback—what sections needed more clarity or explanation, where we'd missed an opportunity to share something cool, a content gap we overlooked because, and such—we moved on to…

Frankendraft™, Stage 5b:

The Read-Through

The final rule of Frankendraft is, “We have to read the entire manuscript word for word, from beginning to end…out loud.”

I have a few reasons for instituting this rule. One of the most important is that reading the words aloud activates a different part of the brain. It allows us to perceive the manuscript with a different part of our conscious mind. It forces us to slow down, to literally hear every word.

My inspiration for the rule came from working with Matthew Pollard on The Introvert’s Edge. Misdiagnosed at an early age with dyslexia, Matthew actually has Irlen Syndrome, a particular sensitivity to light that makes it incredibly difficult to process words on a page (or screen). So, instead of reading my ghostwriting, Matthew loaded each chapter into his text-to-speech program. It made him see (hear?) his book in a different light, generating great ideas and further refinements. Also great for the third level of editing, called copyediting.

Most people simply call it proofreading. To quote Gloria in Modern Family on real estate agents vs. realtors, “There is a difference somehow!” For simplicity’s sake, you copyedit before sending it to the typesetter. After that, it’s proofreading.

Spread over two or three days, the Read-Through allows:

me to do another line editing pass

the author and I to discuss each piece of feedback as part of the whole (instead of examining an isolated paragraph, for example)

my author the confidence that every line, sentence, and word is exactly what they want it to be

And it’s just a great way to end a project.

Of course, it didn’t end there.

Frankendraft™, Stage 5c: Production

Different ghostwriters bow out of the author’s journey at different points.

Traditionally (that is, in the nineties and about a century before that), somewhere around this time, the author would hand their manuscript to their publisher. The author and ghostwriter would shake hands and go their separate ways.

Me? I’m with my author for the entirety of the book’s journey.

With Profound, we had a great publisher. As part of their process, the publisher brought in a wonderful editor, which we welcomed. At this point in a project, I’m blind to the book’s flaws. I may not be the proud poppa, but I am the midwife who helped birth it and the nanny who took care of it in its infancy.

Writing may be an art, but publishing is a business.

When working with a publisher, the explicit goal is to sell as many books as possible. A dance between the author and their publisher does take place. A publisher, for instance, almost always reserves the right to title the book. For good reason: A good title can sell a book all by itself.

In our case, IT Revolution proposed the title Journey to Profound Knowledge with a subtitle similar to what we settled on. (I can’t find the exact proposed original.) We suggested Deming’s Journey to Profound Knowledge to which they readily agreed.

While getting the editor’s marked-up manuscript smarted a bit, it was precisely what the doctor ordered. Like me trimming that other manuscript from 80k words down to 60k, the book had some fat that could stand to be cut out. In addition to the substantive editing, she did a wonderful job further line editing and catching an embarrassing number of “copyediting opportunities,” as I euphemistically like to call my dumb mistakes.

IT Revolution also had a more stringent policy regarding source citations than other publishers I’ve worked with. That meant going back through the books, ebooks, web articles, print-outs, and interviews to create several hundred additional footnotes. Quite an invaluable lesson for me and a challenge I’m grateful I had.

Whenever an editor, proofreader, or anyone else sends back a client’s manuscript, they do it with MS Word’s track changes option turned on, meaning I can see exactly what they changed. I go through every single edit to ensure it aligns with my author’s vision. For 98% of those edits, I simply hit “accept.” For 1%, I hit “ignore.” For the remainder, I get on the phone with my author to discuss how we want to address the suggested change.

For these edits as well as all the feedback from our Alpha Readers, we have three options:

accept as-is

separate the proposed solution from the perceived problem, then decide whether there’s a better way to fix it

ensure we completely understand the issue raised before ignoring it altogether

There may be a few back-and-forths with the editor and/or publisher, but that’s pretty much it.

John and I did all this for Profound, and bittersweetly submitted the final, production-ready manuscript to the publisher. Our journey together had come to an end.

Except it hadn’t.

Life After Frankendraft™

There’s a whole world of professions, tasks, and coordinating to turn a production-ready manuscript into the retail product that is a book, but the Frankendraft framework stops there.

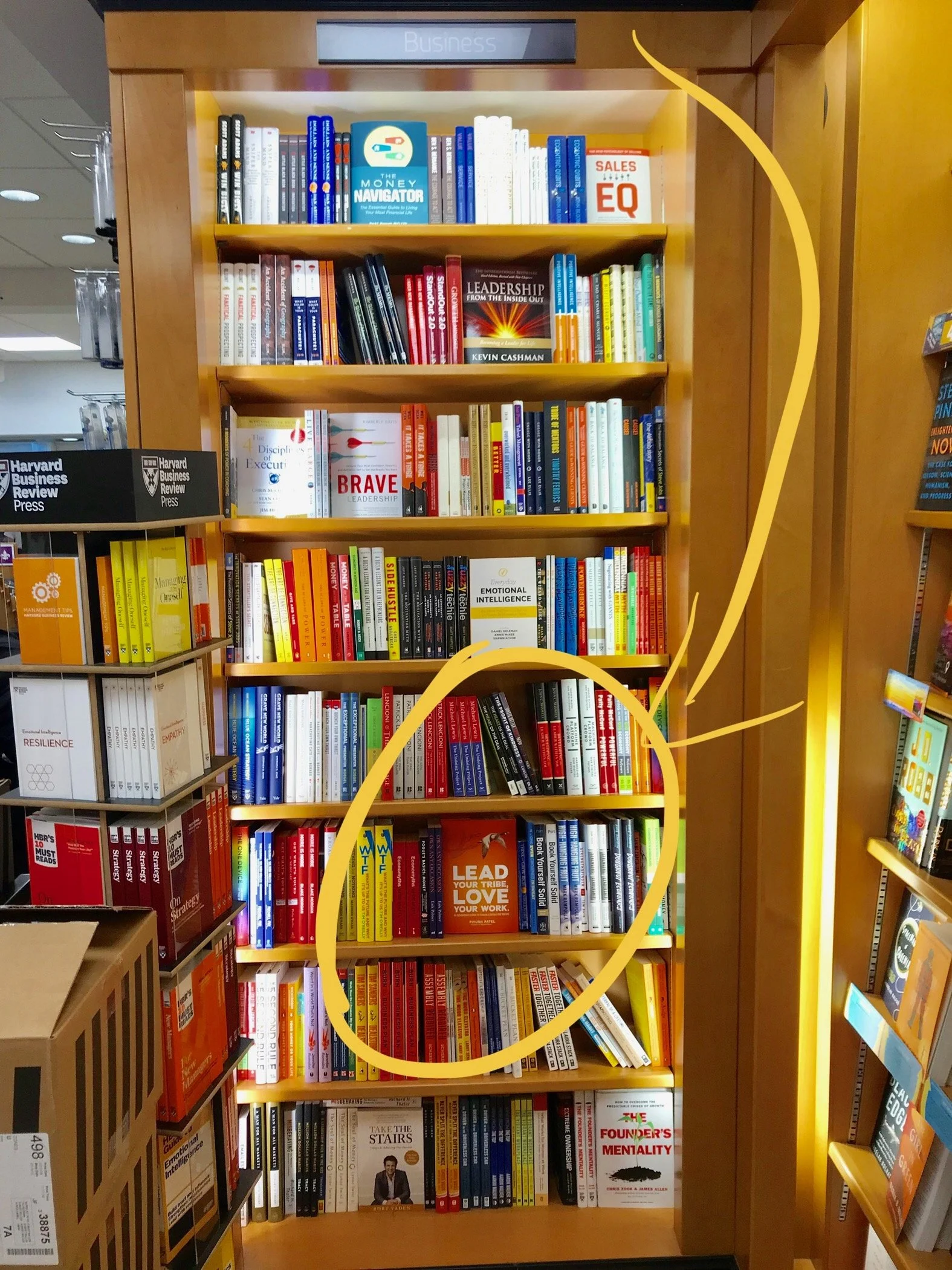

Cover design, typesetting, copywriting, printing, foreign rights, distribution—that’s generally where the machinery of the publishing industry picks up. Generally, all of this has to happen, whether you land a traditional publisher like McGraw-Hill (Redesigning Capex Strategy), choose a boutique publisher like IT Revolution, decide on a hybrid publisher like Greenleaf (Lead Your Tribe, Love Your Work), or self-publish (Neuroselling).

While I don’t provide any of those services, I happily recommend and refer for anyone. For full ghostwriting collaborations, I’m in your corner the whole way. Feedback on cover design, typography, cover copy, or however else I can help. I am, after all, an expert on my own opinion. That’s what I did with John and Profound, from his concepts of an idea to holding it in his hand, I walked with him the whole way.

John loved it so much that he decided to do a second book with me, a memoir of his career in tech startups (Digital Confidential). And then we did Rebels of Reason.

He says,

“I hear people who’ve written a book say they’ll never do that again. They’ll never write another book. I say, I don’t ever want to stop writing books. If you do Derek’s way, it’s fun!”

Hard, as you’ve seen if you’ve read this far. But fun.

What’s It to Be?

Keep Writing Your Way?

Or Would You Like to Have Fun

While You Finally Get It Done?

Red pill, blue pill time, Neo.

If you could write your business book on your own, you already would have.

Otherwise, why would you have come here?

I’m Derek Lewis. I love working with people to turn their expertise into amazing books that people love to read. And I’d love to do the same for you.

I will leave you with a gem from The War Art: “Start before you’re ready.”

Email me at derek@dereklewis.com.

I’m sincerely looking forward to it.